Welcome to the third and final installment of 2019 Big Beers Seminar Experience. If you missed any related seminar or festival experience posts, they can be found below.

2019 Big Beers Seminar Experience Part I: Water Chemistry

2019 Big Beers Seminar Experience Part II: Foraging For Beer

The 2019 Big Beers, Belgians & Barleywines Festival Experience

Ancient Nordic Beer Styles

Aaron Stueck – Head of R&D, BJ’s Brewhouse

Jan Chodkowski – Head Brewer, Our Mutual Friend, Denver, CO

John Bricker – Owner/Head Brewer, Three Barrel Brewing Company, Del Norte, CO

Matthias Hüfner – German Master Brewer, Finland

Josh Cody, Founder and Owner, Colorado Farm Brewery

I will forego the flowery introduction to the seminar in favor of the juicy bits of information I did my best to scribble down, photograph, and jam up in my dehydrated noggin. Please note everything below is as accurate as my transcription, memory, and later research could muster. If you come across any discrepancies, please let me know! This topic is perhaps only slightly less new to me as it might be to you, but it’s just too interesting not to share. 🙂

Sahti

somewhere in between “sahk-thee” and “sah-tee”

History and Ingredients

The word “sahti” essentially means “juice” in Finnish, and is considered a group of grain beverages most commonly brewed in the home. Sahti has its origins in peasant life, and was often created with whatever ingredients the brewers had access to. Hüfner explained, “There are as many different sahtis as brewers.” It is a true representation of Finnish terroir. Though the ancient style allows for a vast amount of variance between representations, there are a few defining features of sahti.

If you were to distill the sahti style down to its basic ingredients, it is a rye beer with juniper (not just the berries!). The grain bill utilizes both malted and unmalted grains, which are processed (or not) at the home of the brewer. These ain’t no store bought components!

The yeast used is not brewer’s yeast, but baker’s yeast! “Hiiva” is Finnish for “yeast”, and a block of Suomen Hiiva is ideal for a traditional sahti fermentation. A very important trait of sahti is the bold presence of isoamyl-acetate, which is the banana-like aroma one might experience from a German hefeweizen. When yeast becomes stressed, it tends to throw off high levels of fruity esters. As such, a bit of yeast stress is essential to a proper representation of sahti. While the popularity of using hops in beer came many years after the sahti tradition began, modern brewers may use hops in the fermentation vessel or to dry yeast on for later use.

Juniper berries are an important part of sahti character, but the boughs and wood chips of the juniper tree are equally, if not more, important. Boughs and branches can be used at the bottom of a mash bed, wood chips can be placed in a mesh bag and used early in the boil, and berries can be used at the end of the boil as well as in post-primary fermentation as a dry spice. The type of juniper used is very important, as some are poisonous, and others simply unfit for flavoring sahti. Overall, American juniper is very aromatic, while Nordic juniper is rather spicy. A bag of common Juniper harvested in Colorado was passed around. I was hesitant to let the bag go – the aromas were punchy and begged to live in beer. I wish Utah juniper was half as aromatic. I suppose it’s easier on the eyes than the palate.

Process

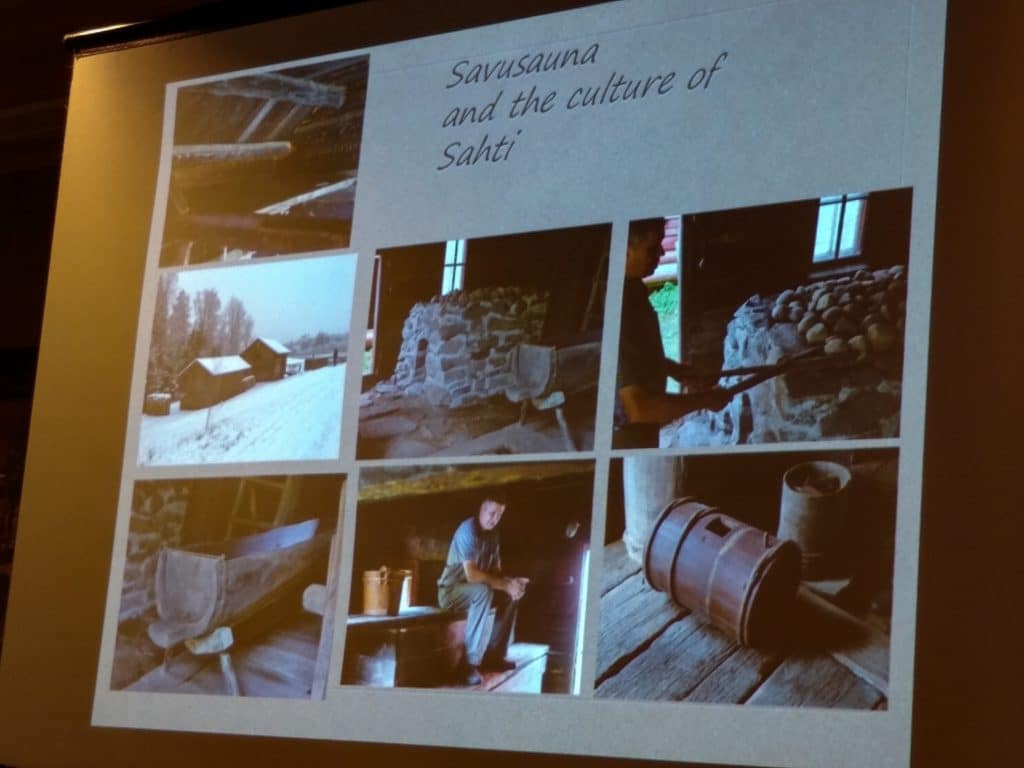

The smoke sauna is and has been an important staple of Finnish culture. Stones kept above a fireplace hearth would get extremely hot, and were used to create steam when water was poured over them. When rye flour was placed on the hot stones, the resulting toasted flour gave a reddish color to the mash. The warm environment was used for drying grains, among many other practices of daily life.

The mash made from house malted or unmalted grain was of a thick, mashed potato-like consistency, and was partially baked before being used for the actual mashing process. The center of the mash loaf (for lack of a better term) still contained the active enzymes necessary for mash conversion, while the outside of the mash loaf provided a toasty, bready character to the finished beer.

The vessel used for the traditional mashing process should be made of wood. Straw is placed on the bottom of the vessel to aid in lautering. Juniper boughs and branches are then placed on top of the straw. The usage rate should equal 2-5% of the grist weight. The mash loaf is then added, I’m guessing broken up in order to increase surface area. Finally, hot water is added on top. Hüfner mentioned with a smirk, if you dip your thumb in and out of the mash four times and it is hot but doesn’t hurt, you’re at the right mash temperature.

For the “boil”, scalding hot stones from the sauna were added either directly to the mash, or to the lautered wort, and the vessel covered to retain heat. The hope was that this would allow the liquid to boil for about 30 minutes.

This technique is very similar to the German steinbier, in which stones are made extremely hot and then lowered into a kettle full of wort to boil the contents. The Germans would take it a step further, and place the same rocks, now coated with a candi-like, smokey caramel, in a lagering tank with the conditioning beer. But that’s for another blog post… 😉

It was noted that barely fermented sahti, which was very sweet, was appropriate for consumption by women. When fermentation was complete, and the alcohol content at its highest, the sahti was considered a drink for men. Those that have modern gender standards that lean toward leveling the patriarchy may sneer (as I did), but you can’t judge history by modern thought, right? Just know I’d drink the sweet, the boozy, and everything in between if I had the chance!

Gottlandsdrikke

“got-land-strick-uh”

Hailing from the Island of Gottland, meaning “good land”, Gottlandsdrikke is the smoky, earthy cousin of sahti. It receives the same juniper treatment as sahti, but with a few other critical additions. Cottonwood smoked malt and dark honey are always used to make this beer. Perhaps most notably, hallucinogens like opium and wormwood were traditional additions. Due to the labor intensive process of making Gottlandsdrikke, as well as its highly perishable nature, commercial offerings are very limited. With the important mind-altering addition in consideration, it’s no wonder this brew remains a homemade specialty.

Stjodalsøl

“shoe-da-shool”

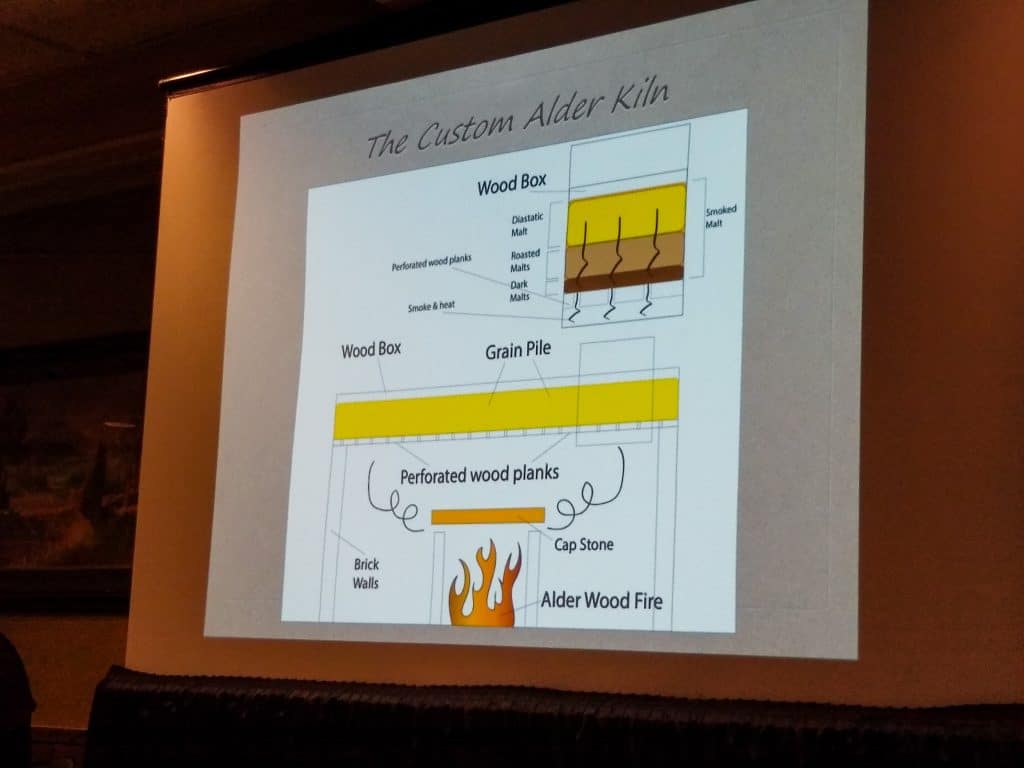

Traditionally brewed on or around Christmas Eve, the Stjodalsøl process begins with kilning malt over an alderwood fire. The kilning takes about 26-48 hours, during which the brewing participants stay up the entire time drinking. The grain being kilned is placed in a shallow wooden box above an alderwood fire. While kilning, the grain is allowed to sit unturned or stirred, which creates layers of malt types. The base malt, or malt that will provide the majority of enzymes to the mash, will be on top. The malt will get progressively darker the closer you get to the bottom of the wooden box. This effectively provides the brewer with both base malt and specialty malt all in one box! Hah! The major issue with leaving the malt unturned is that hot spots tend to appear over time. These spots can easily spontaneously combust, requiring immediate action from the drunken, sleep deprived brewers. If marathon malting were a sport, I think these folks would take the cake!

If you were at all as enamored as I was with ancient Nordic beer styles, then you and I both can eagerly await the June 4th 2019 release of the book titled “Viking Age Brew: The Craft of Brewing Sahti Farmhouse Ale” by Mika Laitinen with a foreword by Randy Mosher. <3

Infinite thanks and love to all panelists, volunteers, and coordinators for opening so many minds to foreign concepts, traditions, and flavors!

[…] branches in the boil and lautering phases of the process. Lauren attended a seminar recently on Ancient Nordic Beer Styles and reported back on what she learned. I invite you to read it if you missed it. Today, many kveik […]