Considering the decades of televised beer marketing and the relatively recent increase of beer nerd wackos that can’t wait to corner you and tell you about that time they stood in line for a quadruple-sour-barrel-aged-double-doggy-dry-hopped-beer for three days, you have probably picked up the ability to rattle off the names of the four main ingredients in beer faster than your home address. But not all beer is as clean and pure as that super-American can of yellow fizz-fizz might lead you to believe. Some beer gets real good and dirty – unabashedly tainted with literal living things that transform those four main ingredients into something miraculously delish… or something so offensive the sink drain doesn’t even deserve it. I’m talking about microorganisms, particularly the ones that are more wild and unpredictable than the standard brewer’s yeast. They’re alive, and they’re doing some real weird stuff to your beer. They are The Beasties Within Your Glass.

Brettanomyces

(breh-tan-oh-my-sees)

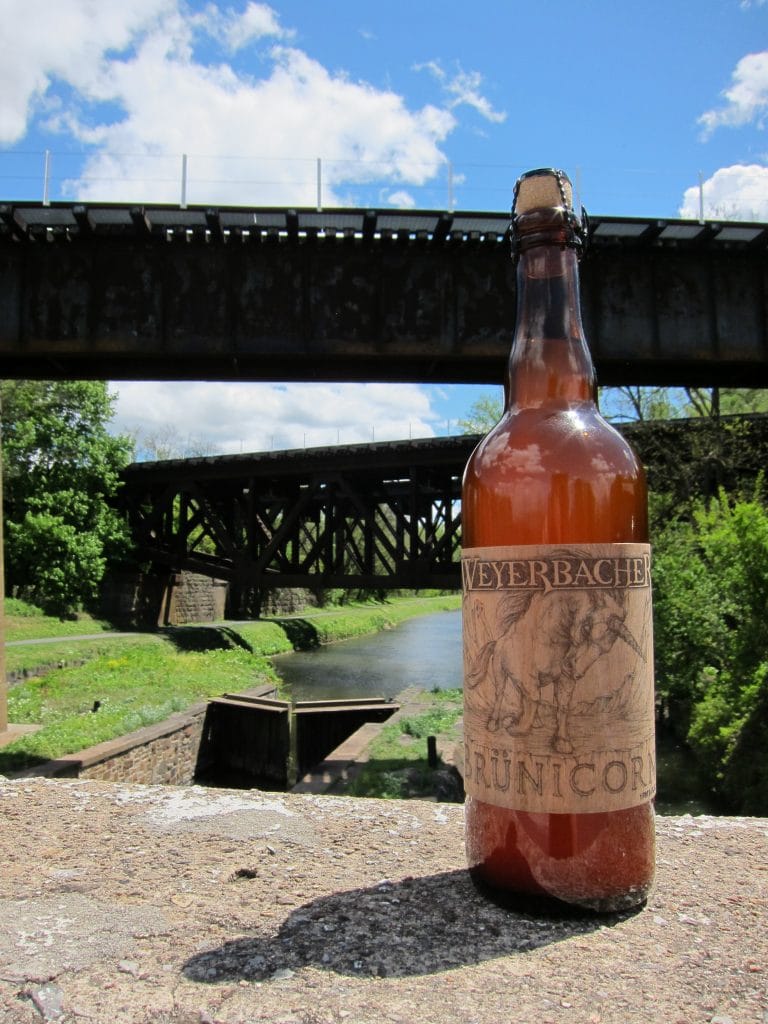

If there’s one beastie you’re already familiar with, it’s likely Brettanomyces (AKA Bretta, Brett, B., wild yeast). Meaning “British fungus”, Brettanomyces grows naturally on the skins of fruit, and has an uncanny ability to eat through sugars and other substances normal brewer’s yeast (Saccharomyces) cannot. Though modern technology and proper sanitation procedures have allowed brewers to break this stallion, the flavors and aromas it can produce are anything but domestic. “Goaty”, “barnyard”, or “horse blanket” are a few of the adjectives used to describe Brett. If you’re already retching, I can’t blame you. But a strange adoration for wilde-Brett is something that comes in the bag of beer nerd wacko tricks. And if you’ve read this far, that includes you. Welcome to the club. Did I ever tell you about the time I drank a whole pint of 10,000 IBU quad IPA?

If there’s one beastie you’re already familiar with, it’s likely Brettanomyces (AKA Bretta, Brett, B., wild yeast). Meaning “British fungus”, Brettanomyces grows naturally on the skins of fruit, and has an uncanny ability to eat through sugars and other substances normal brewer’s yeast (Saccharomyces) cannot. Though modern technology and proper sanitation procedures have allowed brewers to break this stallion, the flavors and aromas it can produce are anything but domestic. “Goaty”, “barnyard”, or “horse blanket” are a few of the adjectives used to describe Brett. If you’re already retching, I can’t blame you. But a strange adoration for wilde-Brett is something that comes in the bag of beer nerd wacko tricks. And if you’ve read this far, that includes you. Welcome to the club. Did I ever tell you about the time I drank a whole pint of 10,000 IBU quad IPA?

(See our blog post about Brettanomyces for more information!)

Acetobacter

(ah-see-toe-bak-ter)

If you’re a kombucha fan, then you’re already friends with Acetobacter. This beastie feasts on ethanol to produce acetic acid, giving your booch that vinegar punch in the mouth. This kick is typically inappropriate for many styles, but is essential to the vino-esque Flanders red. Acetobacter’s kryptonite is the absence of oxygen. An anaerobic environment (one without oxygen) will effectively snuff this puppy’s ability to produce vinegar. As such, the presence of mouth pucker can be evidence your beer came into contact with oxygen when it shouldn’t have (unless, of course, it was intentional).

Enterobacter

(en-tare-o-bak-ter)

(noh-thaenk-yoo)

Enterobacter is not acceptable in the finished product of any beer. If you’ve ever taken a whiff or sip of young lambic, you would understand. There are several strains of Enterobacter, each operating and/or making compounds slightly different from the next. The aromas and flavors produced by this natural but unfathomably fugly microbeast include “moldy”, “fecal”, “vegetal”, and “baby diaper”, among other horrors. Most of these by-products are turned into less offensive compounds by the time lambic fermentation has completed, which takes anywhere from about a year to three years. If your beer that isn’t young lambic smells of poop or rotten veggies, I assume you know what to do. (Run!)

Lactobacillus

(lack-toe-bah-sill-us)

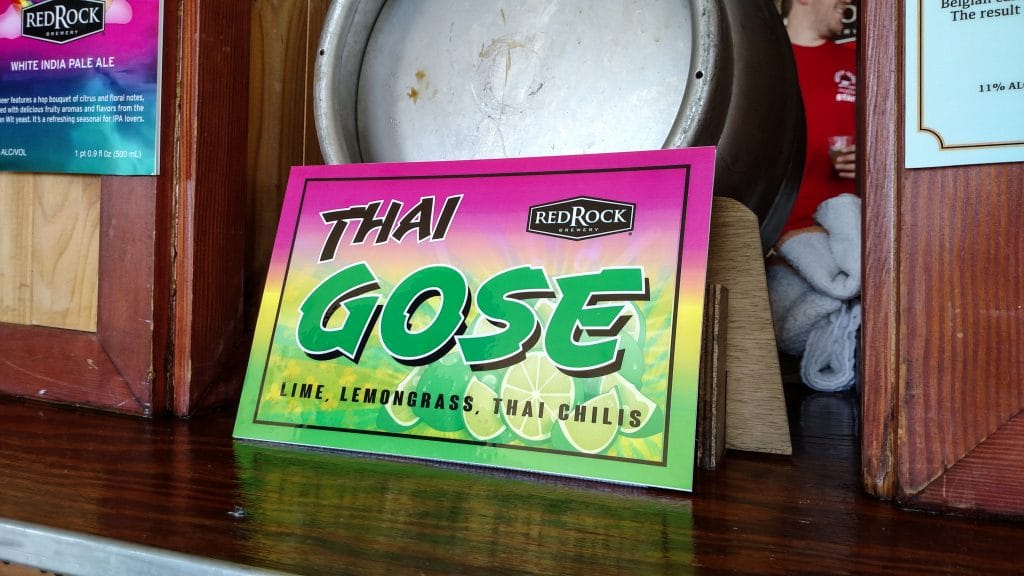

As the name suggests, Lactobacillus creates lactic acid, giving beer a tangy, tart character similar to that of yogurt. This souring critter creates the hallmark flavor of several beer styles, including Berliner weisse (Ber-lin-er vice-uh) and the coriander salt-lick that is gose (goes-uh). Lacto beer is the perfect playground for fruit additions, leaving the consumer with a glass full of sweet and sour beer candy. Brewers use Lactobacillus as a method for souring beer in the brew kettle rather than the fermentation or conditioning vessel, hence the name “kettle sour”. Lacto-beastus plays well on its own, or with other beast friends.

Pediococcus

(pee-dee-oh-cock-us)

Speaking of beast friends, Pediococcus can frequently be seen frolicing around with Acetobacter in the dirty draught lines of negligent bars and restaurants. Pedio converts glucose into lactic acid just like Lacto, but also creates high levels of the buttery off-flavor diacetyl. If you suspect this duo has been practicing their trickery behind the bar and want to forego a shot of sour butter in your next pint of IPA, you might want to stick with cans or bottles. A bi-weekly, thorough cleaning of draught lines will keep these nasties at bay and customers happy.

Not all beasties are baddies. Depending on the brewers intention and the consumers preference, these microorganisms can make for a rather pleasant imbibing experience (except for Enterobacter… ew).

The next time you sit down at the pub and your ear starts to melt from listening to a beer nerd wacko, hit em back with the beasties that go bump in your glass. Talk of Enterobacter is usually enough to quell lengthy conversation… so I suppose it is good for something!

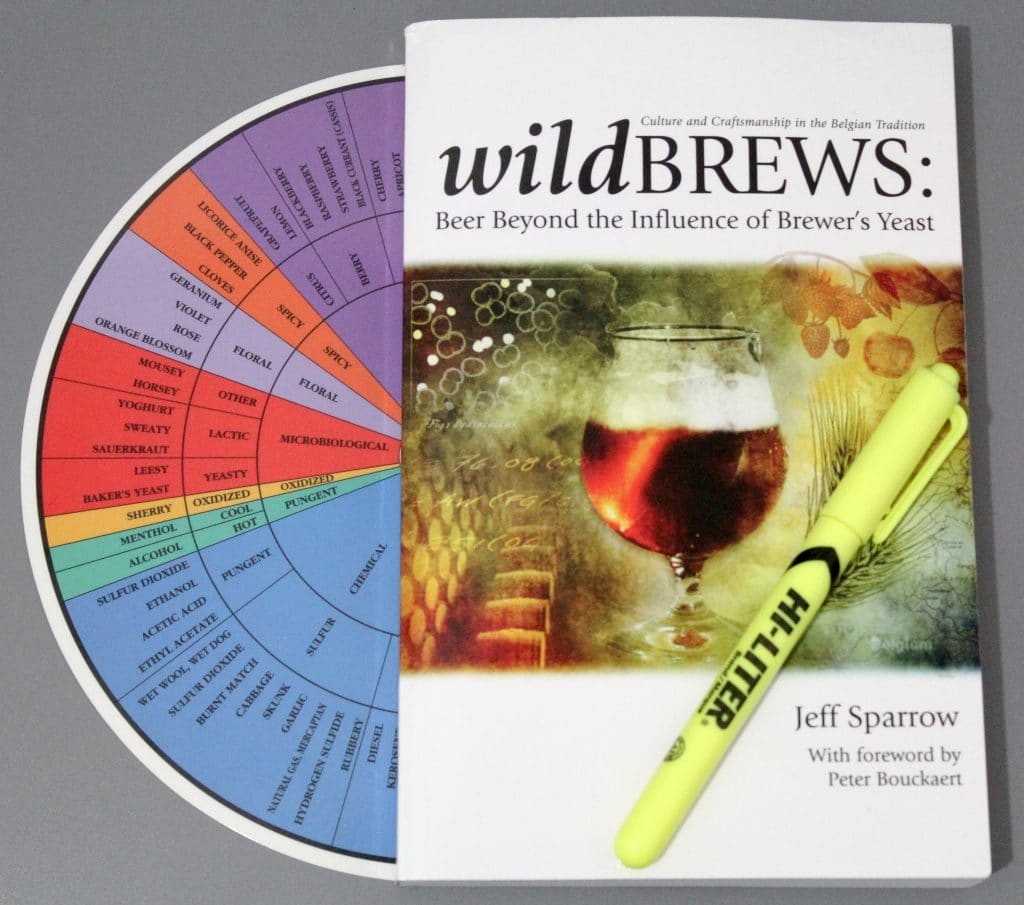

For more on souring microorganisms and the beers they affect, read Wild Brews: Beer Beyond the Influence of Brewer’s Yeast by Jeff Sparrow.

[…] out our previous blog posts, “Who Is This Brett, and What Does He Want with My Beer?” and “The Beasties Within Your Glass”. Those should get you up to speed with our friend/foe, and ready to bust some myths on this beer […]