Before hazy beer roused itself into the spotlight of suds, there was a long era of clear beer. A glass of crystalline pilsner was the perfect window to a sunny afternoon on the patio. Clarity and quality were often seen hand in hand, with several exceptions for brews made dark or with wheat. Clear beer was not made transparent by accident. A beer so fine you can see through it is nothing less than a work of art.

The advent and affordability of clear glass in the 1800s, combined with the new technology to produce light colored malt (and therefore, light colored beer), made way for over two hundred years of clear beer. It was aesthetically pleasing in the glass and a crisp treat to the tastebuds (and still is!). It was the bee’s knees, the cat’s meow, and all other animal parts/sounds associated with something that’s simply great.

Not to poopoo on the haze parade, but somehow opacity has become synonymous with quality in the public eye, giving new meaning to the term “beer goggles”. That’s right – your vision and judgement are askew by the sleight of good beer marketing. I have had a handful of outstanding hazy beers, which require a specific set of tact and knowhow to produce. But cloudiness alone does not qualify a beer as hazy, and this is the mark many producers and consumers miss. In the same sense, clarity of beer alone doesn’t equate to greatness, but it’s certainly a step in the right direction.

There are many methods of giving beer its glassy look. Special equipment and/or specific additives used in conjunction with beer (or wort) throughout the brewing process allow particles of all sizes to be separated from what will end up as the final, clear product. A few of the most common practices are listed here in general order, though others exist.

Lautering

During the brewing process, milled malt mixes with hot water to create mash, which allows the enzymes in the malt to convert starches into sugar. The process that comes next is lautering, or the separation of liquid wort (malt sugar water) from the solid grain matter. A lautering vessel will have a false bottom, which allows liquid and smaller particles to drain through, but not the larger grain bits. The husks from the malt help create a filter bed, further aiding in the separation. The goal is to get clear wort into the wort kettle with as little solid matter as possible.

Kettle Finings

It’s inevitable that some larger bits of grain will make it into the kettle, and the process of boiling also creates hot break (coagulated proteins from the malt). Before moving the wort into another vessel, or to the next step of the process, some brewers add kettle finings shortly before the end of the boil. These kettle finings are made from carrageenan, which comes from seaweed. The fining occurs via electrostatic interaction. The negatively charged carrageenan is attracted to the positively charged protein molecules. This attraction causes flocculation, or clumping. These larger particles will fall more quickly out of suspension, giving better clarity to the wort (see Stokes’ Law). Some commonly used kettle finings are irish moss, koppakleer, whirlfloc, and breakbright. They can come as powder, tablets, or even granules.

Whirlpool

The final clarifying process on the “hot side” of beer production is the whirlpool, which utilizes the “teacup effect”. When the wort is swirled around in the wort kettle or whirlpool vessel, typically via a pump, the solid matter in the wort will tend to settle in the very center at the bottom of the vessel, creating a break or hop cone. After standing for 10-15 minutes, the wort can be slowly removed from the vessel without greatly disturbing the cone, achieving clear wort.

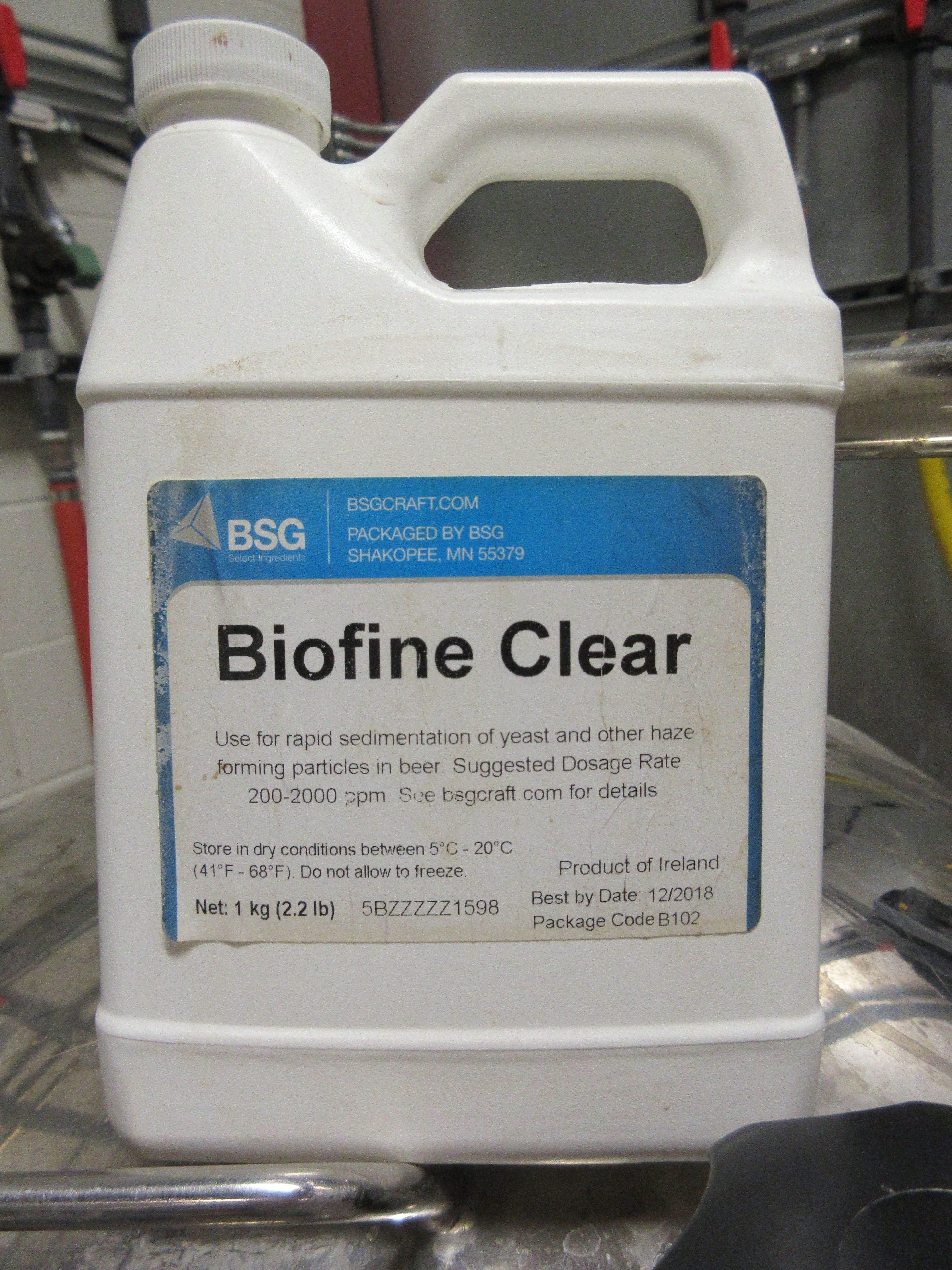

Cold Side Fining Additions

Once the beer has gone through primary fermentation, there are more options for fining beer through additions. Biofine Clear is a viscous, clear liquid that utilizes “a purified colloidal solution of silicic acid” to encourage the settling of suspended particles in the beer. It works best when mixed thoroughly in the vessel. Isinglass is another fining agent, and is a popular addition to cask beer in the UK. It is made from the swim bladder of fish. Don’t worry, it doesn’t make the beer “fishy”. 😉 Acting much like kettle finings, the collagen in the isinglass causes yeast cells to flocculate via an electrostatic action.

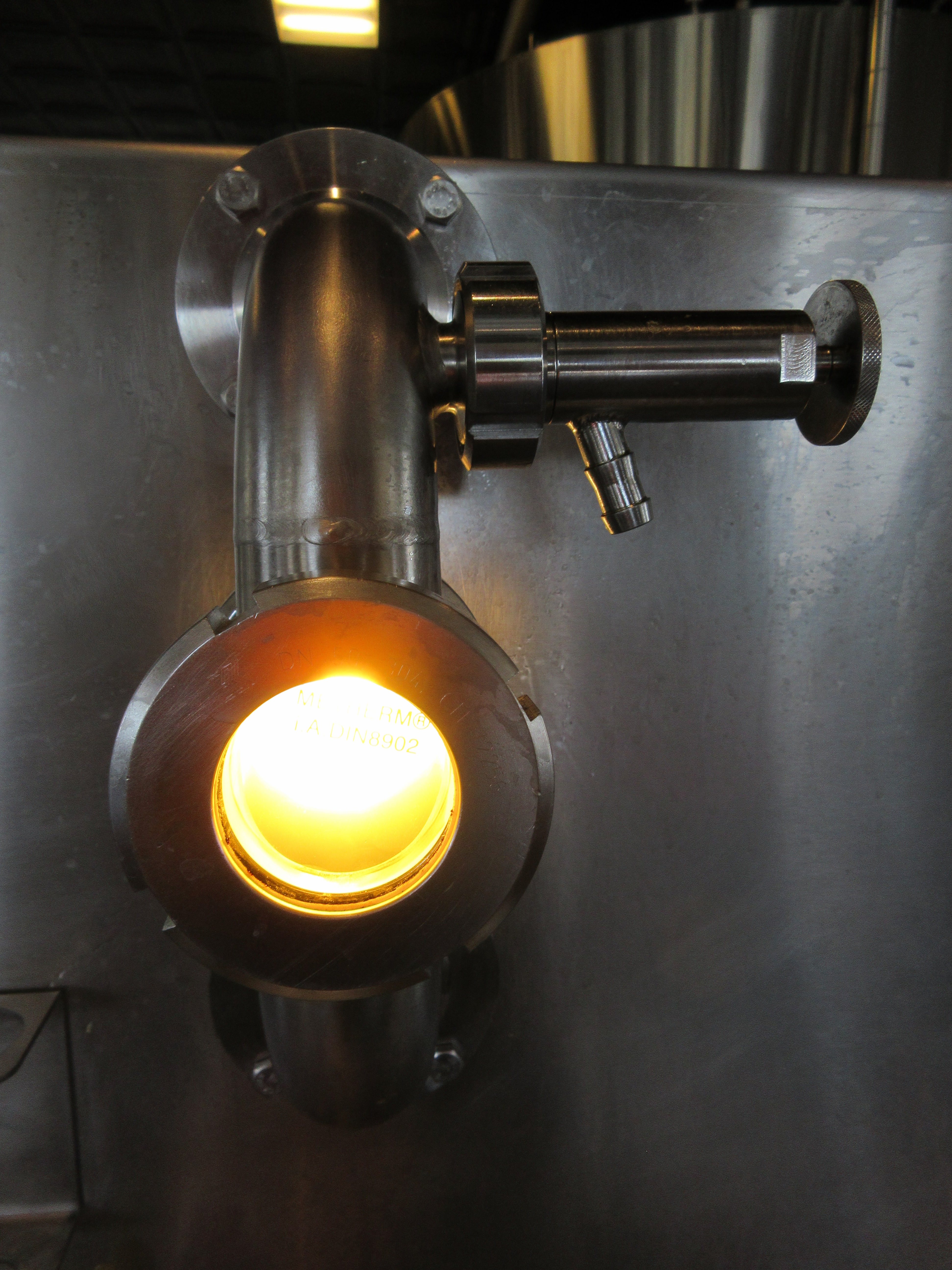

Filtration

One of the final methods of making crystal clear beer is filtration. A centrifuge utilizes (you guessed it) centrifugal force to increase the gravitational pull on haze forming particles, allowing them to separate from the beer before being discharged. The clear beer is passed onto a conditioning vessel or bright tank, though it sometimes continues to another filtration unit called a DE filter. These filters use diatomaceous earth, a.k.a. kieselguhr, which are the fossils of tiny marine organisms that have been crushed into a very fine powder. The inside of the filter is coated with DE, and dosed at intervals while beer passes through the filterbed. The resulting beer is brilliantly clear, just like we want it.

Brewers can use many of these fining options in conjunction with one another, or none at all. Even brewers of hazy New England IPAs use some of these methods to remove astringent polyphenols from their beer. Not all haze forming particles are bad, but some just don’t belong in my glass!

Clear or cloudy, be sure to enjoy it in a beer clean vessel, and to the last sunny drop.

[…] may have read my last post about beer clarity, in which I noted the unfortunate observation that some people have come to believe haze is a sign […]